Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Day: October 29, 2024

In the nearly four years since supporters of former President Donald Trump attacked the U.S. Capitol building, federal prosecutors have indicted at least 35 current or former law enforcement officers for their role in the insurrection, according to an Intercept analysis.

Among their targets was Alan Hostetter, a former California police chief who entered the Capitol grounds with a hatchet in his backpack on January 6, 2021. He was sentenced to more than 11 years in federal prison late last year, among the longest sentences so far out of more than 1,500 prosecutions stemming from the events of that day.

Screenshot: Court filing, U.S. District Court for the Central District of California

Hostetter, who represented himself at trial, spouted a wide range of conspiracy theories during his closing argument, including that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump. The judge overseeing Hostetter’s case emphasized his experience as a police officer during the proceedings. “No reasonable citizen of this country, much less one with two decades of experience in law enforcement, could have believed it was lawful to use mob violence to impede a joint session of Congress,” U.S. District Judge Royce C. Lamberth said in court last year. In July, Lamberth denied Hostetter’s request to be released from prison while he appeals his case, noting that it’s too risky for him to be freed ahead of the “looming” November election. (Hostetter did not respond to efforts to reach him before his conviction.)

Before his journey from police chief in La Habra, California, to insurrectionist, Hostetter spent 22 years at the Fontana Police Department, a small agency in the mostly working-class region southeast of Los Angeles known as the Inland Empire. The area has a history as a hotbed for white supremacist views most commonly associated with the deep South, which have earned it the nickname “Invisible Empire”— a reference to the Ku Klux Klan.

For more than three years, filmmaker Stuart Harmon and I have investigated the culture of policing in Fontana. We spoke with several veterans of the local police department, including four whistleblowers who are featured in a new film published today by The Intercept. We also reviewed hundreds of pages of internal documents, interviewed residents and attorneys, and made several attempts to speak with the police department’s leadership. They declined to answer our questions.

In the aftermath of the 2020 killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, which reignited nationwide protests against police racism and impunity, many departments across the country — including the LAPD and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department — came under renewed scrutiny for officers’ misconduct and abuses. But there are thousands more small-town police departments across the country that are rarely scrutinized, an untold number of them run with near-absolute authority by police leadership whom few residents, let alone officers, have the courage to challenge.

The Fontana Police Department, which in 2013 earned the grim nationwide record for “worst minority representation” among cities with more than 100,000 residents, offers a snapshot of how such departments are run. And as we learned, its history of violence and racism is deeply intertwined with that of the city itself.

Decades of industrial development — and later abandonment — transformed Fontana’s demographics and character from an orange farm town attracting white settlers a century ago, to a booming steel town after World War II, to a trucking hub for warehouses and low-wage shift jobs today.

Throughout the city’s history, demographic change was met with racist backlash. As recently as 1981, men in white hoods marched through downtown Fontana, near the police station — a moment captured in archival photos. A year earlier, a Black lineman was shot by members of the KKK and left paralyzed. The incidents echoed earlier ones, including the burning to death of a Black family in their home, in the 1940s, after they refused to leave their all-white neighborhood.

Today, Fontana is home to a majority Latino population. But the mansion of a former grand dragon of the KKK still stands, not far from the police department — underscoring a point that the late writer Mike Davis, who was born in Fontana, made in his monumental work “City of Quartz.” “The past is not completely erasable,” Davis wrote, “even in Southern California.”

Rare, Unvarnished Testimony

I began looking into the Fontana Police Department days after the January 6 insurrection. Hostetter, who left the department in 2009 after climbing the ranks to deputy chief, had not yet been publicly identified as one of the law enforcement veterans involved, but one of his previous subordinates emailed me a tip about “a White Supremacy group operating at my former police agency.”

David Moore, a 25-year veteran officer who started his career at the LAPD before transferring to Fontana, had come across an investigation I had published years earlier, revealing the FBI’s longtime, quiet probe into white supremacist infiltration of police departments across the country. While the FBI’s involvement was news at the time, the infiltration itself had been an open secret in many of those departments. Moore, who is Black and currently works for a federal defense contractor, didn’t mention Hostetter in his email but wrote instead of widespread racism reaching all the way to the top of the department’s leadership. At times, Moore wrote, that racism crossed the line into white supremacist extremism.

Moore had already described the racism in horrific detail in a discrimination lawsuit he filed against the Fontana PD in 2016. (He amended the lawsuit to charge wrongful termination once he was fired in 2017 in what he says was retaliation for his whistleblowing. In a legal filing, the Fontana PD dismissed many of the allegations around racism as irrelevant to the case. The department settled with Moore and another officer earlier this year, and the case was dismissed in April.)

In his email, Moore laid out a long list of allegations, including that officers routinely used racial slurs to refer to both residents and colleagues of color, and that once, his co-workers had performed a mock lynching of a Martin Luther King Jr. figurine.

One claim in particular was shocking for its cruelty. In 1994, before Moore joined the department, a homeless Black man’s body was found outside a Kentucky Fried Chicken near police headquarters only half an hour after he was released from police custody. He had been fatally choked and later stabbed, according to an autopsy report. When he was taken in for the autopsy, someone placed a half-eaten chicken wing in his hand and took a picture. For years, officers at the department circulated the photograph, which they treated as a joke. An officer who spoke up about the incident told The Intercept he was later forced out.

As Moore grew increasingly disillusioned with department leadership, he began researching the emblems he saw his colleagues sport. He learned that the lightning bolts, runes, and the German eagle that were tattooed on their bodies or featured on their badges were symbols associated with neo-Nazi ideologies. The department’s Rapid Response Team, an elite and notoriously violent unit, displayed as its logo a Nordic owl, another symbol favored by white supremacists.

Moore had denounced all this for years, first internally, then in his lawsuit, and eventually to a local writer, who published the allegations to a muted response. Fontana was a forgotten place, he told me, whose residents, many of them poor and undocumented, are too busy working multiple jobs and fearful of retaliation to openly criticize the department, despite knowing its abuses firsthand.

It is in small departments like this that extremism could fester in silence, he believed. “We must show people in California and the U.S. in general, that White supremacy is alive and active in law enforcement,” Moore wrote. “Very few Officers have the courage to speak out about it.”

Moore, who spent the better part of the last decade embroiled in a fight against the Fontana PD at a huge personal cost, knows from experience why so few officers speak up. Others who denounced problems internally — including his co-plaintiff in the lawsuit, Andy Anderson — were also forced to leave their jobs or resigned out of fear and frustration. One even moved to a police department across the country to get away from Fontana.

We spoke with Moore and Anderson long before they settled their lawsuit, an agreement that neither they nor the police department wanted to talk about. “While the City and its Police Department believe their conduct was in all respects proper and legal, the City’s insurer recognizes the uncertainty litigation presents, as well as costs associated with litigation,” Christopher Moffitt, a lawyer representing the police department, wrote in an email. “David Moore and Andrew Anderson believe a settlement is in their best interest for these same reasons. The Parties have agreed to limit our comments about the lawsuit to this statement.”

Moffitt also said that the police department could not respond to The Intercept’s other questions “in connection with your reporting on the litigation.”

As The Intercept has previously reported, police departments large and small are shrouded in a code of silence that rewards loyalty over ethics. And as a powerful 2021 USA Today investigation exposed, officers who denounce abuse and misconduct by colleagues are ostracized, forced out of their jobs, or worse. Many current and former Fontana officers, Moore cautioned back in 2021, would never speak about what they had witnessed. But he offered to connect me to three who would speak to me on the record, and more who would talk but would not want to be named.

It was a rare offer of access to officers’ unvarnished testimony, now captured in a film that offers an unusually blunt perspective on policing from within — even as it comes from individuals who remain deeply committed to the institution itself.

“Sadly, the silent majority complacently stands by while rogue officers seem to take the lead,” Moore wrote. “This needs to stop.”

The Vital Projects Fund supported the reporting and production of this film.

The post An Insurrectionist Once Helped Lead This Police Department. Insiders Speak Out About Its Culture of White Supremacy. appeared first on The Intercept.

x.com/mikenov/status

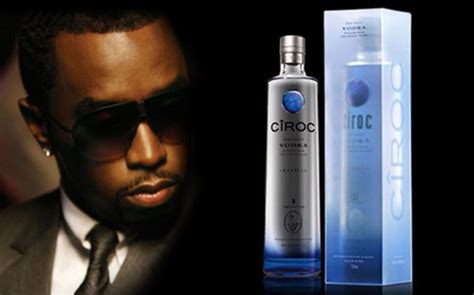

The Hypothesis: Diddy and October Surprise 2024.

Diddy was of interest to GRU and Mossad for some time: 10-15 years. Russian-Jewish Mafia, which serves both the GRU and Mossad, got close to him, got him involved into their Vodka Business, and made the inroads into the Diddy’s inner circle. They set him up to become the “Satan” of the Entertainment Industry and the tool of the massive political and moral discreditation of Democrats, especially, with increasing intensity, during the 1-2 years before the Election 2024, culminating in the “October Surprise 2024”, with the remarkable Media Hysteria, with scapegoating and lynching overtones.

Trump and his services were made the active part of this set up, as Trump possibly hinted himself in his McDonald footage: “I cooked this meal myself!”

What was the FBI’s role in all of that?

Did they get fooled again?

Did they try to shift the responsibility to DHS-HSI?

INVESTIGATE THE INVESTIGATORS!

Russian Alcohol: A Dive Into P Diddy’s Influence And Impact

williamfaulkner

In the world of spirits and liquors, Russian alcohol holds a revered status, known for its rich history and unique flavors. But what happens when this time-honored tradition meets contemporary pop culture? Enter Sean Combs, more popularly known as P Diddy, a mogul whose influence extends far beyond music into the realm of entrepreneurship and luxury branding. P Diddy’s foray into the alcohol industry, particularly with a focus on Russian vodka, has created ripples not just in the entertainment world but also in the global market for spirits. This article delves deep into the confluence of Russian alcohol and P Diddy, exploring how his involvement has reshaped perceptions and consumption patterns.

–

@mikenov: ‘Expect war’: leaked chats reveal influence of rightwing media on militia group | Far right (US)

@mikenov: New Cyber Attack Warning—Confirming You Are Not A Robot Can Be Dangerous forbes.com/sites/daveywin…

@mikenov: Was Diddy Committing Blackmail For The CIA or Mossad? youtube.com/shorts/PSlZh_r… via @YouTube

@BBCWorld: RT by @mikenov: Georgia president calls on Georgians to protest ‘falsified’ election result bbc.in/40nrjKp

@mikenov: Russian Alcohol: A Dive Into P Diddy’s Influence And Impact ftp.metrosportsreport.com/hollywood-didd…

The Supreme Court’s “Presumptive Immunity” Standard

An especially baffling aspect of the Supreme Court’s decision in Trump v. United States is its concept of “presumptive” presidential immunity. The Court ruled that a president’s exercise of “core” powers is “absolutely” immune from prosecution and added that it might hold the exercise of “noncore” powers absolutely immune as well. For now, however, the Court held a president’s use of “noncore” powers only “presumptively” immune. Prosecution of a former president for using a noncore power to commit a crime can proceed if the government can show that this prosecution would pose “no dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.” (I’ll call this standard the “no dangers” test.)

The words “no dangers” underscore the Court’s view that even a slight risk of inhibiting a legitimate exercise of presidential power outweighs the benefit of encouraging presidents to refrain from crimes. As the Court understands the Constitution, legal restraint vanishes when an outside chance of overdeterrence appears. Moreover, the Court required prosecutors to prove the absence of this outside chance without offering a hint of how they might do so.

The Court’s exclusive focus on over-deterrence and its disregard of the risk of under-deterrence are astonishing (especially in light of the facts alleged in Trump’s case), but I maintain in this article that the “no dangers” test isn’t as demanding as it seems. It allows well-founded prosecutions for serious crimes. These prosecutions do not pose a danger of intrusion on legitimate functions of the executive branch.

The “no dangers” test will determine, among other things, whether Special Counsel Jack Smith can present evidence that President Donald Trump pressed Vice President Mike Pence to exclude valid electoral ballots from the official congressional count on January 6, 2021. After ruling that “whenever the President and Vice President discuss their official responsibilities, they engage in official conduct,” the Court declared: “We therefore remand to the District Court to assess … whether a prosecution involving Trump’s alleged attempts to influence the Vice President’s oversight of the certification proceeding in his capacity as President of the Senate would pose any dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.”

Contrary to widespread understanding, the Supreme Court did not hold former President Trump immune from prosecution for any of the crimes with which he is charged in the “January 6” case that reached the Court. These crimes are: conspiring to defraud the United States, conspiring to obstruct an official proceeding, obstructing or attempting to obstruct an official proceeding, and conspiring against the right to vote and to have one’s vote counted. Indeed, the Court did not offer even a word about whether Trump might be immune from prosecution for any of these crimes. The Court’s decision concerned only whether Trump could be prosecuted for acts that were not alleged to be criminal—acts the indictment set forth only as the “methods and means” by which Trump committed the four crimes the indictment did allege. This aspect of the Supreme Court’s decision—its division of the crimes charged into component acts that weren’t themselves alleged to be crimes—has passed largely unnoticed, but I’ll explain why subdividing the evidence was inappropriate. One of the groups of factual allegations treated by the Court as though it were a distinct crime concerned Trump’s efforts to corrupt Pence.[1]

Trump’s Efforts to Corrupt His Vice President

The Special Counsel’s October 2024 brief on presidential immunity and the grand jury’s superseding indictment allege that Trump:

- knowingly made false claims of election fraud;

- knowingly made false claims of Pence’s legal authority;

- repeatedly badgered Pence for refusing to accede to his unlawful demands;

- threatened to criticize Pence publicly, prompting Pence’s Chief of Staff to voice concern for the vice president’s safety to the Secret Service;

- publicly declared “The Vice President and I are in total agreement that the Vice President has the power to act” when in fact they were entirely at odds;

- publicly declared, “If Vice President @Mike_Pence comes through for us, we will win the Presidency”;

- at the urging of advisors, struck remarks he had drafted for delivery to a crowd of his supporters on January 6 concerning the Vice President’s ability to alter the election results—but then reinserted these remarks;

- told the crowd that “if Mike Pence does the right thing, we win this election” and reiterated this claim at least a half-dozen times, prompting the crowd to chant for Pence to return electoral ballots to the states;

- announced that, if the crowd didn’t “fight like hell,” they wouldn’t “have a country anymore”;

- asked the crowd to march to the Capitol;

- learned that Pence had announced publicly that he had no power to judge the validity of electoral ballots;

- learned that a violent riot at the Capitol had begun; and

- tweeted that “Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done to protect our Country and our Constitution,” whereupon rioters chanted “Hang Mike Pence!”; “Where is Pence? Bring him out!”; and “Traitor Pence.”

The Special Counsel’s brief made news by revealing that, when an aide “rushed … to inform the defendant [that Pence had been taken to a secure location] in the hopes that the defendant would take action …, the defendant looked at him and said only, ‘So what?’” But the news accounts omitted the brief’s statement that the government would not use this evidence at trial. Apparently, the Special Counsel recognized that the President’s “so what?” qualified for “absolute” immunity.[2]

The Supreme Court’s View of Trump’s Efforts to Corrupt Pence

Just as President Trump allegedly sought to draw his vice president into a criminal conspiracy, he sought to enlist Republican officials in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. In both situations, he sought to influence actions he had no authority to control, and, in both, his motives and his methods were the same. But the Supreme Court treated the two situations differently. It said that, although Trump’s efforts to corrupt state officials might be regarded as private “campaign conduct” and might therefore be subject to prosecution, his efforts to corrupt Pence were “official” and subject to prosecution only if they passed the “no dangers” test. In other words, the Court left open the possibility that importuning the state officials was unofficial, but it closed the door on the possibility that importuning the vice president was unofficial as well.

The Court noted that “when the Vice President presides over the January 6 certification proceeding, he does so in his capacity as President of the Senate.” It added that “the Vice President’s Article I responsibility of presiding over the Senate is not an executive branch function.” Similarly, it declared that “the Constitution commits to the States the power to ‘appoint’ presidential electors ‘in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.’” It observed that “the President … plays no direct role in the process, nor does he have authority to control the state officials who do.”

As noted above, the Court said: “Whenever the President and Vice President discuss their official responsibilities, they engage in official conduct.” Yet the Court remanded “to the District Court to determine in the first instance … whether Trump’s [effort to influence the state officials] qualifies as official or unofficial.” The Court explained that Trump’s importuning of the state officials might have been “official” because it was “undertaken to ensure the integrity and proper administration of the federal election,” or it might have been “private” because it was “campaign conduct.” In the Court’s view, what might have been campaign conduct when its target was state officials was not campaign conduct when its target was Pence.

The Court offered no explanation of its distinction, but it did describe at length a vice president’s executive branch responsibilities. It noted that Woodrow Wilson’s vice president “presided over a few cabinet meetings,” that Franklin Roosevelt made the vice president a regular participant in cabinet meetings, that Vice President Nixon developed a procedure for relaying important matters to President Eisenhower when Eisenhower was seriously ill, that vice presidents serve as presidential advisors, and that, in the Senate, the Vice President advances the President’s agenda and breaks tie votes. Somehow, these responsibilities made “official” what otherwise might have been campaign conduct. And the Court appeared to be concerned that prosecuting Trump could pose a danger of intrusion on the executive responsibilities it described.

Upon learning of President Trump’s alleged abuse of his vice president, most people’s first thought probably would not be that prosecuting Trump could make future vice presidents less effective in cabinet meetings. But what the Supreme Court seemed to care about—and all it seemed to care about—was the future effective functioning of the executive branch.

The Special Counsel’s View of Presumptive Immunity

The Special Counsel’s brief declared: “Because the Executive Branch has no role in the [proceeding in which Congress certifies electoral ballots]—and indeed the President was purposely excluded from it by design—prosecuting the defendant for his corrupt efforts regarding Pence poses no danger to the Executive Branch’s authority or functioning.” It then devoted six pages to describing the procedure by which the United States chooses a president and the exclusion of the President from this process. It quoted the relevant constitutional provisions, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Joseph Story, James Kent, and Abraham Lincoln.

The point belabored by the brief was one the Supreme Court already had acknowledged, and the conclusion the brief drew from this point appeared to be a non sequitur. Although the Court recognized that Trump sought to influence Pence’s performance of his legislative duties, it said that prosecuting Trump for this conduct might nevertheless pose a danger of intrusion on the authority and functioning of the Executive Branch.

The Special Counsel’s brief addressed this possibility only in a short paragraph, and this paragraph said only “ain’t so”:

[A]pplying a criminal prohibition to the discrete and distinctive category of official interactions between the President and Vice President alleged in this case would have no effect—chilling or otherwise—on the President’s other interactions with the Vice President that implicate Executive Branch interests. The President would still be free to direct the Vice President in the discharge of his Executive Branch functions ….

The Supreme Court’s allocation of the burden of proof made it difficult for the Special Counsel to say more. It is difficult to show that prosecution cannot affect the functioning of the executive branch before anyone has suggested a way in which prosecution might affect the functioning of the executive branch.

The argument on the applicability of the presumptive immunity standard has not really begun. It remains to be seen whether Trump’s lawyers can come up with some conceivable effect on executive-branch functioning.

The Special Counsel’s emphasis on the fact that Trump sought to influence Pence’s performance of legislative duties could be misleading. The next section of this article will show that, even if Trump had sought to influence Pence’s performance of his executive-branch responsibilities, the presumptive immunity standard would not block Trump’s prosecution. (Whether Class A immunity—“Absolute” immunity—would prevent Trump’s prosecution for ordering Pence to take unlawful executive action is a different question, one that the final section of this article will address briefly.)

Making Sense of the Presumptive Immunity Standard

Some observations:

1. The “no dangers” test looks forward, not backward. The Justice Department has determined that a president may not be prosecuted while he remains in office. The issue is whether the prosecution of a former president might affect the work of later presidents or other executive officers.

2. The standard refers only to adverse effects. When prosecuting a former president would do no more than deter later presidents from committing crimes, that effect would supply a good reason for permitting the prosecution, not a reason for blocking it. The words “danger” and “intruding” don’t refer to beneficial effects.

3. The task of proving that no danger exists sounds daunting. Physicists speak of “the butterfly effect,” the possibility that the fluttering of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil can cause a tornado in Texas. But the chance of improper intrusion on executive authority or functioning presumably must be more than de minimis.

4. When the standard speaks of “intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch,” the word “functions” seems more important than the word “authority.” If a former president had authority to do what he did, any statute purporting to restrict what he did would be unconstitutional. If prosecuted, the president would have a defense. In other words, immunity is not necessary to safeguard executive-branch authority. Several doctrines and practices give presidents the benefit of doubt on questions of their authority. The principal function of “presumptive” immunity is therefore to safeguard the proper functioning of the executive branch.

5. Although the Supreme Court did not elaborate the meaning of its standard, it set forth its reasons for approving presidential immunity, and these reasons reveal the sort of intrusion it had in mind. The Court spoke of the:

likely prospect of an Executive Branch that cannibalizes itself, with each successive President free to prosecute his predecessors, yet unable to boldly and fearlessly carry out his duties for fear that he may be next. For instance, Section 371—which has been charged in this case—is a broadly worded criminal statute that can cover “‘any conspiracy for the purpose of impairing, obstructing or defeating the lawful function of any department of Government.’” … Virtually every President is criticized for insufficiently enforcing some aspect of federal law (such as drug, gun, immigration, or environmental laws). An enterprising prosecutor in a new administration may assert that a previous President violated that broad statute. Without immunity, such types of prosecutions of ex-Presidents could quickly become routine. The enfeebling of the Presidency and our Government that would result from such a cycle of factional strife is exactly what the Framers intended to avoid.

The Court emphasized a president’s need to “execute the duties of his office fearlessly and fairly” and “the ‘bold and unhesitating action’ required of an independent Executive.” The evils with which it was concerned were overdeterrence and politically motivated prosecution (sometimes called “lawfare”). “Lawfare” is objectionable regardless of its effect on executive-branch functioning, but, because this sort of prosecution does pose a danger of intrusion on the authority and functions of the executive branch, the presumptive immunity standard bars it along with other prosecutions that might make future presidents too cautious.

6. The kinds of prosecutions that might make future presidents too cautious include: prosecutions for technical violations of regulatory statutes, prosecutions for offenses that aren’t normally prosecuted, prosecutions based on flimsy evidence, and—the Court’s example—prosecutions for violating malleable statutes that prosecutors can shape to cover otherwise appropriate conduct the prosecutors deem corrupt.[3]

7. Prosecutions that do not pose a danger of making future presidents too cautious are: all well-founded, non-discriminatory prosecutions for serious offenses.[4] When a former president has been charged with a serious crime on the basis of substantial evidence, a law-abiding successor would have no reason to apprehend “that criminal penalties may befall him upon his departure from office.” The Court’s “no dangers” test requires a well-founded prosecution for a serious crime, and that’s all it requires. This standard is not as intractable as it may seem.

Could the Supreme Court have doubted that the January 6 prosecution of former President Trump is a well-founded prosecution for a serious crime? Might the Court have believed that a law-abiding successor would view the prosecution of Donald Trump with trepidation that he might be next?

Recall that the Court did not consider Trump’s prosecution as a whole but instead divided the evidence of an overarching criminal conspiracy into chunks and assessed each chunk as though it had been charged as a separate crime. That was an inappropriate way to assess the risk of overdeterrence because it was not the way the Special Counsel had charged Trump’s case and was not the way later presidents and everyone else would understand this case. A future president would not say to himself: “If one part of the evidence of a scheme to steal an election were spun off and charged as a separate crime, I’d be nervous, so I’d better play it safe and abandon my plans to protect the American people.”

Even after the Court’s subdivision of the evidence, each part, viewed separately, seems well supported. But the Court’s disparaging reference to Section 371 (proscribing conspiracies to defraud the United States) suggests that perhaps the Special Counsel should not have drawn his charges entirely from the federal prosecutor’s standard tool kit. Including an easily understood, obviously serious, violent, and readily provable charge of giving aid and comfort to an insurrection would have made it more difficult for the Court to speak of the danger of intrusion on the legitimate authority and functions of the executive branch.

A Note on “Absolute” Immunity

When the Supreme Court held that a president’s exercise of a “core” power is absolutely immune from prosecution, it indicated that the number of core presidential powers is small. Only powers that give the President a “conclusive and preclusive” authority whose exercise neither Congress nor the courts can limit or review are “core.”

The Court drew the concept of “preclusive” presidential power from Justice Robert Jackson’s much admired concurring opinion in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer. That opinion explained (better than the majority opinion in Youngstown) why no presidential power justified President Truman’s seizure of steel mills during the Korean war. Jackson observed: “The example of … unlimited executive power that must have most impressed the forefathers was the prerogative exercised by George III.” Because the Framers were determined not to duplicate that power, neither the commander-in-chief power nor the power to take care that federal laws be faithfully executed was sufficiently “preclusive” to justify Truman’s action.

But the apparent scope of absolute immunity burgeoned like the eggplant that ate Chicago when the Court treated as “absolutely” immune any evidence that Trump had ordered Acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen to send letters to state officials falsely claiming the existence of significant evidence of voter fraud. (Trump had threatened to fire Rosen if he refused to comply with this demand and had desisted only when he realized that carrying out his threat would lead to mass Justice Department and White House resignations.) According to the Court, the President’s conduct was absolutely immune because he had exercised three core powers—the power to decide which crimes to investigate and prosecute, the power to discuss the exercise of this power with Justice Department officials, and the power to remove executive officers whom the President had appointed.

Under the ruling in Trump, the existence of presidential immunity appears to depend on whom a criminal president has attempted to enlist as his accomplices. When Trump lied to induce state officials to join his conspiracy, the Court said that his conduct might be private campaign conduct and subject to prosecution. When, however, Trump instructed his acting attorney general to tell the same lies to the same state officials, the Court ruled that his conduct was not private. It was now official, core, and absolutely immune. The fact that the President sought his own private and political advantage did not matter. The Supreme Court wrote: “In dividing official from unofficial conduct, courts may not inquire into the President’s motives.” A president who has used an official power to accomplish personal objectives has acted “officially,” and, if that power is a “core” power, the crime is laundered and he is home free. Instructing a vice president acting as president of the senate to join in stealing an election is not as beneficial as attempting to enlist an attorney general, but it does afford the President presumptive immunity and therefore may be more advantageous than attempting to enlist state officials.

To put the point differently, pressing a state official to participate in a presidential crime does not launder the crime at all. And pressing a vice president to participate while acting as president of the senate may give the crime only a pre-wash. But pressing an attorney general to commit the crime launders the crime absolutely. The Court’s apparent message to future presidents is that, rather than commit crimes themselves, they should direct executive-branch officials to commit them. A second lesson is that a president should appoint only executive-branch officials who are willing and anxious to commit crimes (Jeff Clarks, not Mike Pences or Jeff Rosens).

What if Trump had directed Vice President Pence to send fraudulent letters to state officials? The President’s order then would have called for executive rather than legislative action by the Vice President. But the Vice President’s position in the executive branch differs from the Attorney General’s. Trump had no authority to fire Pence, and the letters he demanded might have concerned something other than which crimes to investigate and prosecute.

What if Trump had demanded fraudulent letters from others in the executive branch—the Director of the FBI, the Secretary of Agriculture, and a file clerk in the Department of Transportation? Would the concept of a unitary executive bring every criminal instruction to an executive-branch employee under the umbrella of a core power? What if the President sought fraudulent letters from members of the Federal Election Commission, a supposedly independent regulatory agency?

Our wait for answers to these questions may be long. The United States existed for two-and-a-third centuries without prosecuting a former president for a crime, and determining the breadth of absolute presidential immunity may remain unnecessary for another 235 years. The issues that remain open in Trump’s case mainly concern separating private from official conduct and applying the “no dangers” test to conduct determined to be “noncore official.”

Even when artificially separated from the crimes actually charged and envisioned as a separate offense, the prosecution of President Trump for pressuring Vice President Pence to refuse to count valid electoral ballots would be a well-founded prosecution for a serious offense. Applying the “no dangers” test to this hypothesized prosecution should be easy.

- In a judicial first, the Court held that acts can be immune not only from criminal prosecution and from civil liability for damages but also from use in evidence. The Court seemed not to realize that its entire opinion was, in truth, devoted to the question of what evidence of the crimes actually charged would be admissible. Similarly, Justice Barrett, who dissented from the Court’s evidentiary ruling but joined the remainder of the majority opinion, seemed not to notice that the portions of the majority opinion she joined also concerned, at bottom, the admission of evidence. ↑

- If the Special Counsel recognized that this evidence cannot be used, reciting it in his brief seems improper. When immunized evidence cannot be used against a former president at trial, it should not be used against him at all. And presenting inadmissible evidence of politically salient facts for the purpose of informing the public about these facts shortly before an election would depart from the Justice Department’s appropriate nonpartisan role. (Some commentators have criticized the Special Counsel for filing any brief shortly before the election, but, as Andrew Weissmann and Ryan Goodman have shown, that criticism is misguided.) ↑

- Even the expansive immunity approved by the Supreme Court may not do much to protect former presidents from malicious prosecution. It does not block the vindictive prosecution of a former president’s unofficial associates and of family members alleged to be part of his “crime family,” and it does not block the vindictive prosecution of a former president himself for unofficial conduct including activity preceding and following his time in office and activity on the campaign trail. Immunity also does not block the vindictive filing of other charges and the litigation that may be necessary to apply the Court’s labyrinthine standards in one or more courts before a claim of immunity is upheld. ↑

- One indication of whether an offense is “serious” is whether all or almost all known violators are prosecuted, but some serious offenses are rarely prosecuted because they are rarely committed. ↑

IMAGE: The U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., U.S. (Photo credit: Sarah Silbiger/Bloomberg)

The post Does a “Presumptive” Privilege Protect President Trump from Prosecution for Pressuring Pence? appeared first on Just Security.

9AM ET 10/29/2024 Newscast

A data breach at virtual medical provider Confidant Health lays bare the vast difference between personally identifiable information (PII) on the one hand and sensitive data on the other.

The story began when security researcher Jeremiah Fowler discovered an unsecured database containing 5.3 terabytes of exposed data linked to Confidant Health. The company provides addiction recovery help and mental health treatment in Connecticut, Florida, Texas and other states.

The breach, first reported by WIRED, involved PII, such as patient names and addresses, but also sensitive information like audio and video recordings of therapy sessions, detailed psychiatric intake notes and comprehensive medical histories.

The article showed how horrifically compromising some of the information was: “One seven-page psychiatry intake file… details issues with alcohol and other substances, including how the patient claimed to have taken… narcotics from their grandparent’s hospice supply before the family member passed away,” according to the article. “In another document, a mother describes the ‘contentious’ relationship between her husband and son, including that while her son was using stimulants, he accused her partner of sexual abuse.”

IBM’s 2024 Cost of a Data Breach report highlights that 46% of breaches involved customer PII. The report also notes a significant increase in the cost per record for intellectual property (IP) data, jumping from $156 to $173.

But the level of exposure in the Confidant Health incident represents a significant escalation in the potential harm to affected individuals, far surpassing the risks associated with mere PII breaches.

The unique threat of sensitive data exposure

Cyber attackers and bad actors prize sensitive data, including medical data, because it can be used for social engineering attacks, targeted blackmail or even selling to unethical competitors or adversaries. The information’s sensitive nature is precisely what makes it valuable for malicious exploitation.

To be clear, the exposure of sensitive data like medical details is a risk not only to the target but also to their employer. The data can be used to blackmail the employee into providing passwords and other data that can help them in a breach of the employee’s company.

Potential attack vectors include:

- Targeted phishing: Crafting highly convincing phishing emails using knowledge from therapy sessions.

- Blackmail: Threatening to expose sensitive information unless a ransom is paid.

- Corporate espionage: Exploiting personal vulnerabilities of key employees revealed in therapy sessions.

- Identity theft: Combining sensitive data with PII for more convincing identity fraud.

Read the Cost of a Data Breach Report

How to approach data protection

The recent breach serves as a stark reminder of the critical need for robust data protection measures, especially in healthcare settings. The keys are comprehensiveness and constant vigilance.

Protecting sensitive information in healthcare and other settings demands a comprehensive approach.

Authentication

Implementing robust access controls and authentication is crucial. This includes deploying multi-factor authentication for all user accounts and building role-based access controls to limit data access based on job functions. (Regular audits and reviews of user permissions should be conducted to ensure proper access management.)

Encryption

Encryption plays a vital role in safeguarding sensitive data. It’s essential to encrypt data both at rest and in transit, using end-to-end encryption for all communications and data transfers. Device encryption should be implemented for mobile devices and laptops to protect data in case of loss or theft.

Network security

Network security is another critical aspect of data protection. Deploying next-generation firewalls and intrusion detection/prevention systems helps defend against external threats. Network segmentation can isolate sensitive data, while virtual private networks provide secure remote access.

Data loss prevention

Data protection measures should include the implementation of data loss prevention solutions to monitor and control data movement. Data masking and tokenization can be used to protect sensitive information, and regular backups with tested restoration procedures ensure data availability in case of incidents.

Endpoint security

Endpoint security is important for protecting against malware and other threats. Maintain up-to-date antivirus and anti-malware software, implementing endpoint detection and response solutions and using mobile device management for company-owned devices.

Data protection policies

From an organizational standpoint, developing and enforcing comprehensive data protection policies is fundamental. This includes implementing a formal incident response plan and establishing clear data retention and disposal procedures. Regular security awareness training for all employees, with specialized training for those handling sensitive data, helps foster a culture of security consciousness throughout the organization.

Risk management

Risk management is an ongoing process that involves conducting regular risk assessments and vulnerability scans. A formal risk management program should be implemented, with regular updates and patches applied to all systems and software.

Third-party risks

Managing third-party risks is equally important. This involves implementing strict vendor risk management procedures, ensuring all third-party contracts include data protection clauses and regularly auditing third-party access and data handling practices.

Compliance

Compliance and auditing are critical components of a robust security program. Organizations must ensure compliance with relevant healthcare regulations, such as HIPAA. Regular internal and external security audits should be conducted, and detailed logs of all data access and system activities should be maintained.

Data governance

Data governance is essential for effective data protection. This includes implementing a formal data classification system, establishing data ownership and stewardship roles and regularly inventorying and mapping all sensitive data.

Incident response

Incident response and recovery capabilities are crucial for minimizing the impact of security breaches. Organizations should develop and regularly test an incident response plan, establish a dedicated incident response team and implement automated threat detection and response capabilities.

Physical security

Physical security measures should not be overlooked. Securing physical access to data centers and sensitive areas, implementing proper disposal procedures for physical media and using surveillance and access control systems in critical areas are all important aspects of a comprehensive security strategy.

Keep sensitive data safe

By implementing these measures, organizations can significantly enhance their data protection posture. However, it’s important to remember that cybersecurity is an ongoing process that requires constant vigilance. Regular assessments and improvements to the security program are essential to maintain robust protection of sensitive information in the ever-evolving landscape of cyber threats.

As we navigate an increasingly digital landscape, this incident highlights the urgent need for a paradigm shift in how we view and protect sensitive data. It’s no longer enough to focus solely on safeguarding PII. Organizations must adopt a holistic approach that recognizes the unique value and vulnerability of sensitive personal information.

The post Why safeguarding sensitive data is so crucial appeared first on Security Intelligence.