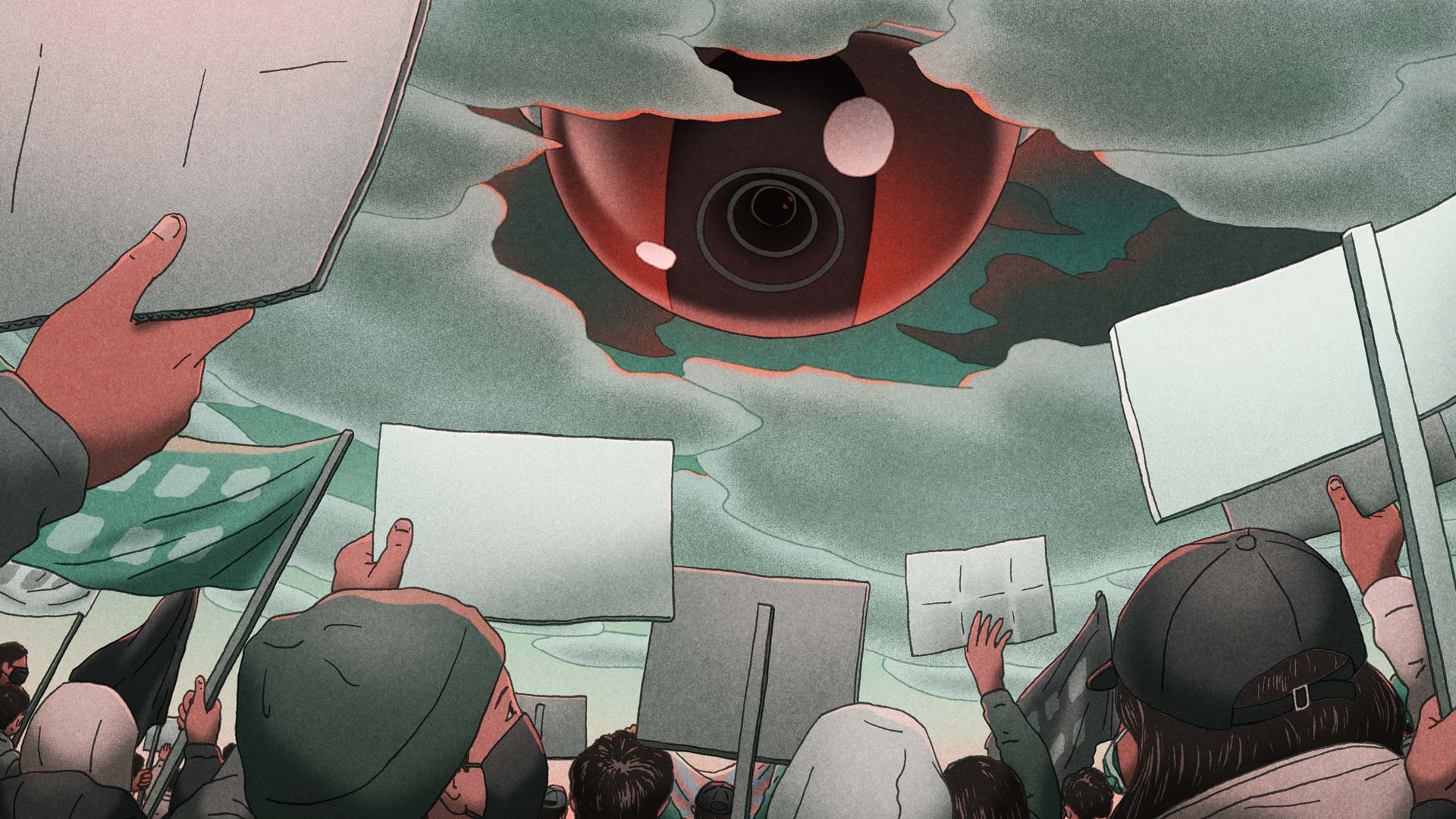

The targeted repression of human rights activists across borders is becoming more frequent and sophisticated, according to the latest annual U.N. report detailing acts of intimidation and reprisals inside the international organization.

The report lists new allegations of reprisals from two dozen countries including China, echoing the findings of ICIJ’s China Targets investigation, which revealed how suspected proxies for the Chinese government surveilled or harassed activists at the U.N. headquarters in Geneva, the center of the human rights system.

Two Hong Kong pro-democracy activists and a Uyghur linguist are among the cases compiled by the secretary-general between May 2024 and 2025, alongside updates on reprisals included in previous reports.

“Allegations of transnational repression across borders have increased, with examples from around the world,” the report said. “Targeted repression across borders appears to be growing in scale and sophistication, and the impact on the protection of human rights defenders and affected individuals in exile, as well as the chilling effect on those who continue to defend human rights in challenging contexts, is of increasing concern.”

Raphäel Viana David, the China and Latin America program manager at the International Service for Human Rights, a nonprofit that trains activists in U.N. advocacy, said the report reflected a shift within the U.N. in recognizing transnational repression as a tool states use to carry out reprisals.

“The assistant secretary-general — who is the senior focal point on reprisals — when she presented the report at the Human Rights Council a couple of weeks back, emphasized this angle of transnational repression,” Viana David said. “This is an interlinkage that I think is increasingly evident, but that needs a little bit more disentangling.”

In China Targets, ICIJ and 42 media partners exposed how Beijing has misused international institutions such as the U.N. and Interpol to target overseas dissidents. The investigation included interviews with 105 individuals across 23 countries who detailed how the Chinese government had reached beyond its borders to silence them.

Viana David said that discussions about the prevalence and impact of transnational repression at the U.N. began gaining traction last year, prompting the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to publish a brief aimed at identifying and addressing the problem in June.

The new U.N. reprisals report describes how two senior employees of the Hong Kong Democracy Council, a Washington-based nonprofit that supports democracy in the region, allegedly experienced repeated acts of retaliation from the Chinese government for their involvement with the U.N. ICIJ has previously reported on Beijing’s efforts to silence senior international advocacy associate Carmen Lau.

In late December 2024, the report said, the Hong Kong government labeled Lau and the council’s executive director, Anna Kwok, as fugitives for their work promoting democracy and independence in Hong Kong and offered a bounty of roughly $130,000 each for information leading to their arrests. The pair have also had their passports revoked. The Hong Kong government previously issued an arrest warrant for Lau in 2021 over allegations of election interference.

Lau told ICIJ that the attacks had impacted her security, financial stability and freedom of movement. She said that police had also interrogated members of her family still living in Hong Kong.

Lau’s neighbors in London received pamphlets urging them to provide the Hong Kong government with details that could lead to her arrest, she told ICIJ. She also said she has been the target of a coordinated digital surveillance and smear campaign and has had her social media accounts compromised. The U.N. report noted that in March 2025 a video “apparently generated by artificial intelligence” that mimicked Lau and depicted her making false statements to discredit her was widely shared on social media.

“There were letters sent to my neighbors here in the U.K. encouraging them to bounty hunt me, and it had all sorts of my personal information, including my precise, then-residential address,” Lau said. “As an activist, I was very, very careful about my digital footprint, and I’m exceptionally cautious about my personal data security. So it was very frightening at first when I learned that they have my address and precisely my neighbors living in the same block as me.”

Lau said the attacks have had a chilling effect on other dissidents living in the U.K. who fear that Beijing could also target their family members at home.

“To the broader Hong Kong diaspora, because of these acts of retaliation, it actually silences and poses a sense of fear amongst the people,” Lau said.

The Chinese government told the U.N. in July that Hong Kong police follow strict legal procedures and that Hong Kong opposes any external interference or attempts to influence its judicial process, according to the report.

The government of Hong Kong said in a statement to ICIJ that it “strongly condemns any smearing of our work in safeguarding national security,” and that Lau and Kwok “are wanted because they continue to blatantly engage in activities endangering national security and collude with external forces to cover for their evil deeds.”

The Hong Kong police acknowledged an ICIJ request for comment but did not respond before deadline.

The U.N. reprisals report also detailed an alleged incident at an international language technologies conference co-organized by the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in February 2025 at its Paris headquarters. Abduweli Ayup, a Uyghur linguist and activist who fled China in the mid-2010s after 15 months in detention, said that a group of unidentified individuals at the conference questioned him about his family’s whereabouts after he voiced concerns over the Chinese government suppressing the teaching of the Uyghur language. China has long faced scrutiny on the global stage for its discrimination against Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group native to the northwest Xinjiang region, including through mass detention and forced labor.

Ayup was told by conference organizers that they were unable to secure approval for him to give a presentation on his research, according to the U.N. report. Ayup alleged that UNESCO canceled the presentation without giving him a reason. He presented it the following day during a coffee break the following day. He told the OHCHR and ICIJ that someone he didn’t know filmed him speaking and followed him for the remainder of the conference.

In a statement to ICIJ, UNESCO said that Ayup’s presentation was not canceled and that a miscommunication had resulted in the delay. UNESCO said an internal investigation was conducted after the incident and that no evidence of wrongdoing was found.

“UNESCO only became aware of this claim because of the reprisals reporting procedure, several weeks after the incident in February,” the statement said. “UNESCO takes the safety and security of all its visitors — at Headquarters, and during its conferences — very seriously.”

A spokesperson for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights said in a statement to ICIJ that the office takes allegations of intimidation and reprisals against those who engage with the U.N. very seriously and provides protection advice and support to victims of reprisals.

Responses to reprisals vary across the U.N. system, the spokesperson said, noting that some facets of the international body are working to strengthen their internal procedures to respond more effectively.

“While challenges remain, the UN continues to advocate for stronger protections and accountability, and to support civil society actors who courageously engage with the Organization,” the spokesperson said.